Giving effective feedback

Introduction

Feedback is a vital part of education and training. This module offers some suggestions on how you can improve the feedback you give so that you are better able to help motivate and develop learners’ knowledge, skills and behaviours.

By the end of the module, you should have:

- Learned and updated some of the principles behind giving effective feedback and establishing a ‘feedback culture’

- Considered the different contexts in which feedback can be given

- Thought about some of the issues involved in giving and receiving feedback

- Had an opportunity to apply the learning from the module to your own practice through carrying out activities and reflecting on these

Before you start

Before you start the module we recommend that you spend a few minutes thinking about the following points and noting down some of your thoughts.

| Thinking points |

|

WHAT IS FEEDBACK?

Feedback is an essential part of education and training programmes. It helps trainees maximise their potential at different stages of education or training, raises their awareness of strengths and areas for improvement, and identifies actions to be taken to improve performance. It can be directive, which informs the trainee of the aspects of performance that require correction, or facilitative, which helps the trainee develop their practice.

Feedback may be written, verbal or numerical.

To maximise learning, feedback should be specific to the task yet help the trainee to make connections to related tasks or contexts. It can be informal (for example in day-to-day encounters between trainers and trainees, between peers or colleagues, or from patients) or formal (e.g. as part of summative written or clinical assessment). The somewhat artificial distinction between summative and formative (developmental) feedback has been unhelpful and we now see that (whilst it is necessary to hold formal assessment and feedback events) good feedback is part of the overall dialogue or interaction between trainer and the trainee and not simply a one-way communication.

Giving structured, formal feedback can help reinforce, modify and improve behaviours although feedback can also have negative, unintended consequences if it is not given or received in a safe and constructive way. Although feedback is necessarily about observed performance, good feedback is forward-facing (‘feeding forward’), helping the learner identify new goals, improvements or actions.

If we don't give any feedback, what is the trainee gaining, or indeed, assuming?

They may think that everything is OK and that there are no areas for improvement. Trainees value feedback, especially when it is given by someone credible who they respect as a role model or for their specific knowledge, behaviours or clinical competence. Failing to give feedback sends a non-verbal communication in itself and can lead to mixed messages and false assessment by the learner of their own abilities, as well as a lack of trust in the teacher or clinician.

Most trainers already give feedback to trainees. This module offers some suggestions on how you can improve the feedback you give so that you are better able to help motivate and develop learners’ knowledge, skills and behaviours.

Why is feedback so important?

Feedback is central to developing trainees' competence and confidence at all stages of their training. Many clinical situations involve the integration of knowledge, skills and behaviours in complex and often stressful environments, with time and service pressures on both trainer and trainee. Feedback doesn’t have to be formal, it can be a quick nod, smile or word of encouragement.

However, the more formal purpose of giving feedback to trainees is so that they think about the gap between actual and desired performance and identify how they can narrow the gap and improve.Trainees value feedback that helps them develop, facilitates self-reflection and motivates them to learn more and improve.

One of the main purposes of feedback is to encourage reflection. Gordon notes that:

Just as many learning opportunities are wasted if they are not accompanied by feedback from an observer, so too are they wasted if the learner cannot reflect honestly on his or her performance. One to one teaching is ideally suited to encouraging reflective practice, because you can model the way a reflective practitioner behaves. Two key skills are (a) ‘unpacking’ your clinical reasoning and decision making processes and (b) describing and discussing the ethical values and beliefs that guide you in patient care. (2003, p. 544)

Grounding feedback within an overall approach that emphasises ongoing reflective practice helps learners to develop the capacity to critically evaluate their own and others’ performance, to self-monitor and move towards professional autonomy.

| Thinking point |

| How do you and colleagues embed reflection within learning and clinical activities? What challenges are there in doing so in busy clinical or academic environments? |

Feedback and the Learning Process

It is very important to ensure that the feedback given to the trainee is aligned with the overall learning outcomes of the clinical activity in which the trainee is engaged. Giving feedback is part of experiential learning which, for health professionals, involves ‘learning on the job’ and purposefully reflecting on situations, feelings and various experiences.

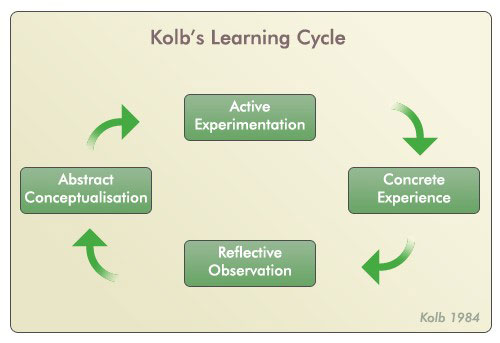

Kolb (1984) proposed that learning happens in a circular fashion, that learning is experiential (learning by doing), and that ideas are formed and modified through experiences. These ideas underpin the idea of the ‘reflective practitioner’ and the shift from ‘novice to expert’ which occurs as part of professional development.

The learning cycle requires four kinds of abilities or learning contexts:

- Concrete Experience – learners are enabled and encouraged to become involved in new experiences (‘ok, you have watched me manipulate a shoulder a number of times, now I’ll watch you do it with the next patient’)

- Reflective Observation – gives learners time to reflect on their learning (‘how do you think that went? Could you feel the resistance there...what might you do next time, more of, less of.....’)

- Abstract Conceptualisation – learners must be able to form and process ideas and integrate them into logical theories (‘let’s think about the anatomy again, describe the joint structure to me .... how does what you were feeling and doing relate to the anatomy?’)

- Active Experimentation – learners need to be able to use theories to solve problems and test theories in new situations (‘the next patient has a frozen shoulder; how do you think you’ll approach this one in relation to the previous patient and your learning?’).

Remember, the learning might start at any point in the cycle - you might review the anatomy and rehearse the steps in the procedure with the trainee before they see the patient.

This cycle is similar to the ‘plan – do – reflect – review’ cycle which is often used in appraisals. It is important to note that the points in these cycles are not necessarily sequential and that in practice one or more activities may be occurring at the same time. However, feedback at various points is very important in helping learners develop competence e.g. feedback supports the process of reflection and the consideration of new or more in-depth theory and can also help the learner plan productively for the next learning experience.

If we consider that one of the tasks of those giving feedback is to help the learner achieve their learning goals, then Hill (2007) suggests that we need to start with an understanding of:

(a) where the learner is in terms of their learning, the level they have reached, past experience, and understanding of learning needs and goals (this is a 3rd year medical student who is on their first medical ward, very different from a final year student who is qualifying in three weeks’ time)

(b) the learning goals in terms of knowledge, technical skills and behaviours. You may be observing more than one of these learning domains at the same time (‘I’d like you to carry out the pre-operative checklist on the next patient, I’ll watch how you do it and particularly focus on how you give her accurate information and reassurance about the operation’).

During the observation, our task is to identify where and how far the learner has travelled towards the learning goals, where they may have gone off track and what further learning or practice may be required.

WHO GIVES FEEDBACK?

- Trainers

- Clinicians from a range of healthcare professions

- Patients

- Peers and colleagues

- The trainee themselves

- Others?

| Thinking point |

|

Archer (2010) suggests that health professions must move on from merely addressing the ‘performance gap’ to nurturing ‘recipient reflection-in-action’ – a developmental dialogue between teacher and learner.

This is a key part of an integrated approach to establishing and supporting a ‘feedback culture’ in which teachers, programmes and organisations need to embed feedback activities and opportunities in day-to-day working and learning, and that feedback must be ‘conceptualised as a supported, sequential process rather than a series of unrelated events’ (2010, p106). This brings us to the idea of a ‘learning journey’ as part of a lifelong learning approach.

In ‘Assessing Educational Needs’ the concept of trainers helping trainees to develop their ‘self-efficacy’ which typically involves some form of self as well as external assessment. Eva et al (2008; 2012) note the importance of framing feedback in terms of individual receivers, who will (because of personality, background, culture and experience) be very different from one another. This is not always as straightforward as it may seem because of a range of interacting factors including power relations, anxiety or cultural and personality differences.

Barriers to Giving Effective Feedback

| Thinking point |

| When you are given feedback, what do you think acts as a barrier to receiving it constructively? |

Hesketh and Laidlaw (2002) identify a number of barriers to giving effective feedback:

- a fear of upsetting the learner or damaging the learner-teacher relationship

- a fear of doing more harm than goodthe learner being resistant or defensive when receiving criticism. Poor handling of a reaction to negative feedback can result in feedback being disregarded thereafter

- feedback being too generalised and not related to specific facts or observations

- feedback not giving guidance on how to rectify behaviour

- inconsistent feedback from multiple sources

- a lack of respect for the source of feedback.

Feedback must be given sensitively and appropriately and it is important to acknowledge the relationship aspects between trainer and trainee.

Trainees are often in a dependent and subordinate role and it is easy to dismiss issues of organisational power and authority that often underpin work relationships. This is particularly important if the organisational culture is bureaucratic, hierarchical or results-oriented, as in healthcare, where there are often tensions around professional role boundaries and status.

Those giving feedback and the recipients need to be clear about expectations and aim to develop a supportive, relaxed and informal environment. Recipients also need to have and show respect for the person giving feedback, for example when multi-source feedback is being used. Some trainees might be quick to dismiss feedback from certain groups or individuals.

Other differences between the person giving feedback and the recipient include sex, age or educational and cultural background. These are not necessarily obstacles, but they may make feedback sessions difficult, strained or demotivating.

Receiving Feedback

This module is mainly about giving effective feedback to trainees, but more recent research suggests that it is helpful to focus on how feedback is received.

Many models start with asking the recipient to assess their own performance and, whilst this is a traineer-centred approach, there are risks, particularly if trainees do not receive sufficient regular, routine feedback from external sources,that they will not have enough understanding to self-assess. In order for professionals to effectively self-monitor and evaluate their own performance, they need to move from individual, internalised self-assessment to self-directed assessment-seeking behaviours. This is best achieved through ongoing, regular, supportive external feedback from a range of reliable and valid sources.

Sometimes feedback is not received positively or acted upon by trainees, and this can inhibit trainers giving regular face-to-face feedback. Learners often discount their ability to take responsibility for their learning, and their responses may present in negative ways, including anger, denial, blaming or rationalisation. Eva et al note that differing interpretations or uptakes of feedback may be based on a number of factors including personality factors, fear, confidence, context and individual reasoning processes (2012). People’s responses to actual or perceived criticism, however constructively it is framed, can vary. Trainees with high emotional stability, responsibility and sociability are more likely to be motivated to seek feedback and use it constructively. When giving feedback therefore, it is helpful to maintain an empathic yet consistent approach with a view to helping trainees take responsibility for development and improvement.

The aim of developing an open dialogue between the person giving feedback and the recipient is so that both parties are relaxed and able to focus on actively listening, engaging with the learning points and messages, and developing these into action points for future development. You can help to prepare trainees (and yourself) for receiving feedback by providing opportunities for them to practise the guidelines listed below.

Guidelines for receiving constructive feedback

- Listen to it (rather than prepare a response/defence).

- Ask for it to be repeated if you did not hear it clearly.

- Assume it is constructive until proven otherwise; then consider and use those elements that are constructive.

- Pause and think before responding – your aim is to have a professional conversation that helps you.

- Ask for clarification and examples if statements are general, unclear or unsupported.

- Accept it positively (for consideration) rather than dismissively (for self-protection).

- Ask for suggestions of ways you might modify or change your behaviour.

- Respect and thank the person giving feedback.

Feedback Models

A number of practical models exist for giving feedback.

- The ‘feedback sandwich’, which starts and ends with positive feedback. The more critical feedback is ‘sandwiched’ between the positive aspects. Recipients often report however that they are simply waiting for the negative and thus the positive feedback is diminished or unheard. ‘I noticed that you made the relatives feel very comfortable before you explained the procedure to them and your explanation was very clear. It would have helped if you had provided the information leaflets, as at times they were looking a bit bewildered. However, you have set a time for meeting with them again, and this will give you the opportunity of answering any questions and taking the leaflets’.

- Reflecting observations in a chronological fashion, replaying the events that occurred during the session back to the learner. This can be helpful for short feedback sessions, but you can become bogged down in detail during long sessions.

- Another model for giving feedback in clinical education settings that you may have come across was developed by Pendleton (1984). This is more learner-centred, conversation based and identifies an action plan or goals: ‘reflection for action’.

Pendleton’s ‘rules’

- Check the learner wants and is ready for feedback.

- Let the learner give comments/background to the material that is being assessed.

- The learner states what was done well.

- The observer(s) state(s) what was done well.

- The learner states what could be improved.

- The observer(s) state(s) how it could be improved.

- An action plan for improvement is made.

- Walsh (2005) summarises a model for giving feedback to groups:

- Start with the learners’ agenda.

- Look at the outcomes that the session is trying to achieve.

- Encourage self-assessment and self-problem solving first.

- Involve the whole group in problem solving.

- Use descriptive feedback.

- Feedback should be balanced (what worked and what could be done differently).

- Suggest alternatives.

- Rehearse suggestions through role-play.

- Be supportive.

- The session is a valuable tool for the whole group.

- Introduce concepts, principles and research evidence as opportunities arise.

- At the end, structure and summarise what has been learnt.

Although these models are useful frameworks, some are formulaic and when giving feedback to individuals or groups, an interactive approach as in model 4 or the structured debrief used in simulation is most helpful.

This approach helps to develop a dialogue between the learner(s) and the person giving feedback and builds on the learners’ own self-assessment; it is collaborative and helps learners take responsibility for their own learning.

Principles of Giving Effective Feedback

Whether or not you use a practical model and are giving formal or informal feedback, a number of basic principles should be kept in mind.

- Give feedback when the learner is ready (this may be physically, practically or emotionally) so that they are likely to be receptive.

- Give feedback as soon after the event as possible, although for knowledge consolidation, a delay can be beneficial.

- Ask the trainee how they think things went first; this will open the conversation and let you see how well the trainee is judging their own performance.

- Focus on the positive first.

- Give feedback privately wherever possible, especially more negative feedback.

- Feedback needs to be part of the overall communication process and ‘developmental dialogue’. Use skills such as rapport or mirroring, developing respect and trust with the trainee.

- Stay in the ‘here and now’ and on the observed task, don’t bring up old concerns or previous mistakes, unless this is to highlight a pattern of behaviours.

- Focus on behaviours that can be changed and the task itself, not personality traits.

- Talk about and describe specific behaviours, giving examples where possible and do not assume motives.

- Use ‘I’ and give your experience of the behaviour (‘When you said…, I thought that you were…’).

- When giving negative feedback, suggest alternative behaviours.

- Feedback is for the recipient, not the giver – be sensitive to the impact of your message.

- Consider the content of the message, the process of giving feedback and the congruence between your verbal and non-verbal messages.

Encourage self-reflection. This will involve posing open questions such as:

(a) Did it go as planned? If not, why not?

(b) If you were doing it again what would you do the same next time and what would you do differently? Why?

(c) How did you feel during the session? How would you feel about doing it again?

(d)How do you think the patient felt? What makes you think that?

(e) What did you learn from this session?

- Be clear about what you are giving feedback on and link this to the learner’s overall professional development and/or intended programme outcomes.

- Do not overload – identify two or three key messages that you summarise at the end.

Giving Formal Feedback

Observations over a period of time or for specific purposes (e.g. workplace-based assessment, practical sign-offs, appraisal, end of placement interviews) are typical situations when formal feedback occurs in the clinical setting.

If ongoing feedback has been carried out regularly, then the formal feedback sessions should not contain any surprises for the learner. It is increasingly common for trainees to decide when they are ready to be assessed for competence and sign-off of many workplace procedures (such as airway management, drug administration, dietary or nutritional patient assessments) and to arrange assessments with their trainers. Feedback can be given on a one-to-one basis or in small groups.

The structure for giving feedback should be agreed in advance and may follow one of the models described above. It is also important that both you and the trainee(s) to whom you are giving feedback are fully prepared for the session.

Trainers are at times required to participate in formal clinical assessments (including in skills laboratories) which should incorporate feedback to the trainer.

Below is an example of how this may be carried out.

Setting up a formal clinical assessment session incorporating feedback

Prior to the session you should:

- ensure the trainer is aware they are being assessed and will receive feedback (so clearly define the purpose of the feedback session prior to or at the outset of the session)

- collect any information you need from other people

- ensure you know the trainee’s strengths and areas for development/improvement

- make sure you know how the feedback relates to the learning programme and defined learning outcomes.

Setting the scene:

- create an appropriate learning environment

- clarify your ground rules with the trainee as to what they are to concentrate on, when you will interrupt, what other students are to do, how the student can seek help during the consultation, etc.

- agree a teaching focus with the learner

- gain the patient’s consent and co-operation

- make notes of specific points to cover.

Once the assessment is finished, during the formal feedback session, you should:

- redefine the purpose and duration of the feedback session

- clarify the structure of the session

- encourage the trainee to self-assess their performance prior to giving feedback

- aim to encourage dialogue and rapport

- reinforce good practice with specific examples

- identify, analyse and explore potential solutions for poor performance or deficits in practice.

After the session, you should:

- carry out any agreed follow-up activities or actions

- make sure that opportunities for remedial work or additional learning are arranged

- set a date for the next assessment/feedback session, if required.

Giving Informal Feedback

Many opportunities exist for giving informal feedback to learners on a day-to-day basis. Such techniques often involve giving feedback to trainees on their performance or understanding, with feedback being built into everyday practice and conversation. Those giving feedback can help the trainee to move through the stages in the ‘competency model’ of supervision (Proctor, 2001; Hill, 2007) as shown in the table below.

| Unconscious incompetence | Conscious incompetence | Conscious competence | Unconscious competence | |

| Trainee | Low level of competence. Unaware of failings | Low level of competence. Aware of failings but not having full skills to correct them | Demonstrates competence but skills not fully internalised or integrated. Has to think about activities | Carries out tasks with conscious thought. Skills internalised and routine. Little or no conscious awareness of detailed processes involved in activities |

| Feedback giver | Helps trainee to recognise weaknesses, identify areas for development and become conscious of incompetence | Helps trainee to develop and refine skills, reinforces good practice and competence, demonstrates skills | Helps trainee to develop and refine skills, reinforces good practice and competence through positive regular feedback | Raises awareness of detail and unpacks processes for more advanced learning, notes any areas of weakness/bad habits |

Providing informal on-the-job feedback can take only a few minutes of the trainer’s time. It might be fairly instructional and ‘in the moment’ (‘well done’, ‘a bit to the left’, ‘think about what we talked about with Mr Y’). To be the most effective, feedback should take place at the time of the activity or as soon as possible after so that the trainee and the trainer can remember the events accurately. The feedback should be positive and task-specific, focusing on the trainees’ strengths and helping to reinforce desirable behaviours: ‘You made sure that you kept Mrs X fully informed during the procedure, I feel this helped to reassure her…’.

Archer’s (2010) review however identifies that high-achieving trainees undertaking complex tasks might benefit from delayed feedback rather than immediate feedback on steps in a sequence, which can inhibit performance and learning.

Negative feedback should also be specific and non-judgemental, possibly offering a suggestion: ‘Have you thought of approaching the patient in such a way…?’. Focus on some of the positive aspects before the areas for improvement: ‘You picked up most of the key points in the history, including X and Y, but I noticed you did not ask about Z…’. Unless a learner is putting someone at risk, avoid giving negative feedback in front of other people, especially patients.

Keep the dialogue moving with open-ended questions: ‘How do you think that went?’, which can be followed up with more probing questions. Hesketh and Laidlaw (2003) also suggest that learners should be encouraged to ‘seek feedback themselves from others… feedback actually works best when it is sought’, reflecting the principle of encouraging self-directed assessment-seeking. You may need to support some learners in doing this more than others and direct them towards people who will be supportive at first to help build up their confidence and competence.

Summary

This course has considered the role of feedback in the way in which doctors develop confidence and competence. Feedback is vital for learning, both from external sources as well as in the development of accurate self-assessment skills. Whilst much of the focus on feedback is as part of formal or summative assessments (which in themselves can be improved), this course highlights that the most effective feedback is embedded into day-to-day practice and professional conversations, is forward-facing and forms part of a culture of feedback and learning.